Christmas in Connecticut (1945), directed by Peter Godfrey, written by Adele Comandini and Lionel Hauser from a story by Aileen Hamilton.

Every year over the first weekend in December, Janice and I spend an exhausting weekend making her incredible chocolate truffles, then we order a pizza and watch Christmas in Connecticut. It’s a delightful cinematic confection starring Barbara Stanwyck, Dennis Morgan (whom Janice adores) and great character actors, including S. Z. “Cuddles” Sakall. It concerns a woman who writes about food but can’t cook, falls in love, and the trouble she gets into on Christmas.

Here’s how this romantic and heartwarming comedy opens:

In the cold Atlantic, a Nazi submarine torpedoes an American destroyer. Hundreds of sailors perish from burning alive, sustaining blunt-force trauma from the shock waves or being torn apart by shrapnel. Those who survive the attack freeze to death or drown in the cold waters. Two sailors, Jefferson Jones (Morgan) and Sinkewicz, aka “Sinky” (Frank Jenks), make it to a small inflatable raft. They dream of eating luxurious food. Jones, Sinkewicz’s superior, offers up his last K-rations in an attempt to save his friend. They are on the raft for 18 days, over two weeks, with little or no sustenance.

The men are rescued and brought to a stateside hospital. Here Jones subsists on a diet of raw eggs suspended in milk, while his pal Sinky enjoys steaks and chops, in part because of the fact that he ate Jones’ K-rations and didn’t starve for 18 days and presumably didn’t wreck his stomach. Desperate for a real meal, Jones plays ruthless psychological games with Mary Jane (Joyce Compton), a nurse, promising to marry her if she will only get him meat and potatoes for dinner. She succumbs; Jones’ first bite of steak nearly kills him and he almost chokes to death until Sinky saves him.

Eager to avoid marriage to a woman he never loved (and presumably now eating solid food), Jones claims that he’s an artist and a painter and afraid of marriage. Desperate to get Jones to commit to her, Mary Jane remembers that she once was a nanny to the children of powerful publisher Alexander Yardley (Sidney Greenstreet). She requests that Yardley ask the top columnist at his Smart Housekeeping magazine, Elizabeth Lane (Stanwyck)—whose articles about cooking captivate a hungry, rationed nation—to take in Jefferson Jones over Christmas in an attempt to get him to see the beauty of home life, which will make him want to marry her. Yardley loves the idea of entertaining a true American hero, and forces his employee to host the sailor at her home in Connecticut over the holiday, and cook him a dinner fit for a king.

Elizabeth Lane can’t cook. She’s also not married and has no child. Happy with this arrangement, she lives in a cozy walk-up in Manhattan with a loud radiator. Her best friend, Felix Bassenak (Sakall), is a Hungarian chef who writes all her recipes. When her boss, Dudley (Robert Shayne), finds out that Yardley wants Elizabeth to host a sailor at her Connecticut home, he races to her and begs her to come up with some reason to convince the publisher not to do this. Because if Yardley, a stickler for the truth, discovers she can’t cook and has no hubby, Elizabeth and Dud will both be out of a job. She tries, but she can’t stop his plan from unfolding, because Yardley gets what he wants, always.

Since this is a romantic comedy, there has to be milquetoast suitor cast aside by the woman in order to get the man she truly wants. In this case it’s John Sloan, architect (Reginald Gardiner, who made a career of playing thrown over men). He wants to marry her and she agrees, reluctantly, since she thinks she’s about to lose her job. Soon, Elizabeth, Jefferson Jones, Sloan, Felix, two real babies who aren’t hers, Alexander Yardley, Sloan’s housekeeper Norah (the great Una O’Connor) and a friendly cow all descend upon this lovely Connecticut home for some food, companionship and goodwill. What could go wrong?

Well, everything, of course. And it works, in part because I think Warner Bros. wanted an upbeat holiday movie in this last year of the second World War (the public was growing real tired of war films by this time), and assigned its workers to make it happen, who did so, and happily. Honestly, Christmas in Connecticut is as much a product as a coat or a car or a pair of shoes. I mean, Peter Godfrey directed it, Lionel Hauser and Adele Comandini wrote it, it was shot by Carl E. Guthrie and was scored by Friedrich Hollaender. With all due respect, that’s about as serviceable a group of filmmakers as you’re going to find. Edith Head is the only behind-the-scenes personality of note, as Stanwyck had a clause in her contract that Head made her outfits and no one else, no matter the studio.

Thankfully, Warner Bros. brought together a crack cast: Stanwyck is, of course, awesome, but for those not in the know, Dennis Morgan’s Jefferson Jones is a real charmer. Morgan never really gained a foothold in Hollywood, he was a clean-cut fellow whose singing style went out of favor in the 1950s, that kind of high-pitched stuff no one listens to today, either. Born in Prentice, eventually he was inducted into the Wisconsin Performing Artists Hall of Fame. So there you go.

Then you have Sydney Greenstreet, Cuddles Sakall and Una O’Connor supporting the stars. Everyone knows Greenstreet, the fat man from The Maltese Falcon, his reputation from that film trailing after him so doggedly that Sakall’s Felix actually mutters “Fat Man” under his breath in this movie. Una O’Connor was everyone’s favorite crazy servant, with a heavy Irish brogue and bugging her eyes out at the slightest malfeasance (she’s perhaps most famous for Bride of Frankenstein).

And the sets! Again, the art director, Stanley Fleischer, and the set designer, Casey Roberts, didn’t exactly have a need to find room in the den for Oscars—their credit list is fraught with mediocrities that no one watches today and probably didn’t much then, either. Off the top of my head, I can’t think of a film with warmer sets, spacious interiors brilliantly designed to allow the characters to roam but also create a sense of luscious coziness in the viewer. From Elizabeth’s bright Manhattan apartment with its steamy windows and hissing radiator; to Restaurant Felix, one level below the city streets and filled with Hungarian bric-a-brac and a buffet to die for; to Sloan’s Connecticut rambler with its enormous fireplace, exposed beams, sunny kitchen and warm den, whose fire blankets a sleepy Felix with a warm glow later in the picture. Contrast this with Yardley’s cold mansion, which he’ll abandon for the holiday home of Elizabeth Lane and husband.

I love watching the story unfold in these places. Felix wandering happily around his restaurant, checking on his staff, comforting Elizabeth and her boss when they think they’re going to lose their jobs (for lying about her marriage, baby and ability to cook). There’s a surprising scene in Restaurant Felix, one of the very few from this time with a Black character who isn’t a caricature.

I used to have a blurry YouTube video of this, but it went away. Emmett Smith plays a young man named Sam, who is working for Felix. As Elizabeth enters his restaurant, Felix asks how things are. “Catastrophe,” she says. Felix, always sunny, smiles and repeats the word, and asks Sam what it means. “It’s from the Greek…” Sam says, and then proceeds to explain its meaning. “It’s good, yeah?” Felix says. “No, sir. That’s bad.”

I bring up this scene because there’s a lot of modern attitudes in Christmas in Connecticut (yes, to go along with its decidedly dated attitudes). Smith, above, was Black, and like a lot of Black character actors, was relegated to demeaning parts—his credits include Ramar of the Jungle and Jungle Queen or he’s reduced to playing a red cap in No Man of Her Own (yet another Stanwyck masterpiece). Here, he is clearly an educated man, simply working in a restaurant.

And Elizabeth Lane is her own person, a great writer who doesn’t take crap from anyone, and when she sees and desires Jefferson Jones, doesn’t hide her lust—”are you the type who kisses married women?” she asks Jones. She’s clearly hungering for that kiss and disappointed the dumb fool won’t give it her, though probably that’s because the Hays code kept him from doing so.

The silly chaos of this plot—subterfuge, lying, Elizabeth and Sloan about to be married once, twice, thrice, thwarted so that she can marry Jones, who thinks she’s already betrothed, babies and a kidnapping that’s not a kidnapping—all of this is leavened by quiet scenes of our characters eating and drinking, playing cards and smoking with a brandy while the windows frost up, walking the property to put away a wandering cow, decorating a Christmas tree. I could stare at this stuff for hours.

Then there’s the sense of community. We love watching people get along in tight groups, with witty and warm conversation, going about their day and being pals—we’ll watch hours of mediocre TV that does nothing else. Here, we go from Restaurant Felix, with its huge staff and patrons who look like regulars, to the people of this Connecticut town, where later we go to a town hall for a dance and War Bond rally. Manhattan and Connecticut feel like places we want to be.

Supposedly, Greenstreet and director Godfrey entertained the cast and crew during filming, and everyone had a delightful time. That radiates from the screen, this sense of affection and the pleasure of being in a movie, working hard on something fun, nothing too serious. And Christmas in Connecticut was an enormous hit. People came in droves to escape the drudgery of four years of war, bad news, rationing, the terrible yellow telegrams, all the accoutrements of the worst conflict in human history up to that point.

All of this is wonderful because, truly, Christmas in Connecticut gets a lot wrong, doesn’t make sense, is clumsily thrown together, and, at times, has baffling scenes. It has the worst movie blocking I’ve ever seen, multiple shots of Greenstreet saying a line and then standing stock still and facing away from the camera, his enormous back filling half the screen. When people aren’t talking, they tend to stand around like mannequins. Early on, Jones says that he is an artist and a painter, but is that true? It’s never brought up again. There’s sure a lot of pointless running.

And this year I couldn’t help but wonder—was everyone so immune to the violence of World War II that they could laugh at the opening? Or was this part of the damaging propaganda that has continued to shape minds even today? Yes, at the home front, people were not told of the casualties to the degree we are today, and they were not always privy to the carnage going on overseas. There was essentially no TV and obviously no internet. This wasn’t Vietnam, it was World War II, and the propaganda machine was running at its most ruthless and efficient. This movie does reinforce the idea that you could endure a ship’s being blown up, then starve for over half a month, and be carefree and successful in your post-war life. Film noir this ain’t.

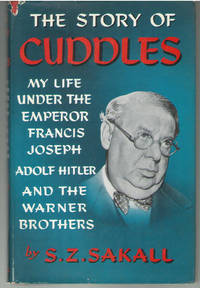

But maybe this was also a genuine attitude of the time. Consider Cuddles. One of my favorite character actors, S. Z. “Cuddles” Sakall found a great role in Felix the restauranteur and friend of Elizabeth. He was also in Casablanca and somewhat miscast as the shop owner in In the Good Old Summertime, among many other roles. In Christmas in Connecticut he’s hilarious, making his funny faces and his funny noises and later, toward the end of the movie, Felix is drunk and asleep, playing solitaire in the den of the Connecticut farmhouse den, lit by the fire, in a Christmas Eve vision that makes me feel so cozy and comfy I often rewind the movie just to watch him drop off to dream of goulash and red wine.

But in life, Mr. Cuddles Sakall had a turbulent life. Perhaps my favorite Hollywood autobiography is his very out-of-print The Story of Cuddles: My Life Under the Emperor Francis Joseph, Adolph Hitler and the Warner Brothers. I read it again just this last week. It’s written in such a plain, happy style, that at times I had to read twice his tales of suffering, which aren’t embellished at all. His mother died when he was young, then his father married his wife’s sister (whom everyone called Aunt Emma). His father was a sculptor who made gravestones. When Cuddles was a boy, a group commissioned a model from his father, for a statue that was to grace a public park. They gave him money to buy clay for the study to determine whether they would want to pay for the final stone statue. But his dad squandered the money on clothes and food and treats for his family and didn’t have money for clay anymore. What to do? Well, the night before he was to present his model there was an enormous snow storm, so the elder Mr. Grünwald (that’s the family’s real name—S. Z. Sakall means “blond beard” in Hungarian) molded a statue out of snow that wowed the jury, who awarded him the contract and gave him more money.

That money came in handy, because working through the night on the snow gave father pneumonia, and he was dead in a week.

Cuddles was stabbed in the chest in hand-to-hand combat in World War I and watched his first wife die within a year of marrying her. His family nearly starved and he somehow made it to the United States, avoiding death at the hands of the Nazis. As of publication, every one of his immediate family, including all his brothers and sisters, was dead. His biography, in spite of these facts, is one of the most upbeat books I’ve ever read about a person’s life.

I think, then, that Christmas in Connecticut’s lighthearted look at suffering is a degree of propaganda, but it also truly reflects how people endured the hardships that befell them back then. My own Grandpa Schilling was in Normandy, a medic who saw such incredible violence he could only speak of it to one person in my family. His diaries read similarly to Cuddles’ book—he writes of “the Skipper Upstairs” who helped get him through D-Day, and enjoyed the hell out of Hogan’s Heroes later in life. I mean, seriously, how do you go through all this trauma and emerge without losing your mind? Maybe with laughter. Not always, but sometimes.

I watch Christmas in Connecticut’s opening scene, of the ship being torpedoed, and I think that there must have been someone who was sitting in the dark theater, a sailor who’d survived such an attack and saw a good friend or friends die, a woman who remembers the telegram informing her that her husband or brother or son was lost at sea. Maybe that scene triggered them, and then the next hour and a half soothed them, made them remember that there is food and friendship in life and that helped them.

Then again, maybe not. You don’t have to look too hard to see how people who survived that war turned into alcoholics and suffered debilitating PTSD.

Obviously, I don’t know what everyone thought about Christmas in Connecticut back in the 1940s, but I’ve seen it once a year every year for the last ten to fifteen holidays, making it most likely the film I will see more than any other in my life, which I find very strange even as I write it. We tend to be very forgiving of holiday movies, and even the most fragrant pile of shit gets reappraised if it’s a Christmas movie.

But Christmas in Connecticut is one of those rare pictures that speaks to the joy of Golden Age filmmaking, of working together and having a good time even with bland material, of finding the simple joys of people, of food, of love, and celebrating it, especially at a time when the world is devouring itself. If that’s not a gift, I don’t know what is.

Excellent insights and information. I was amazed to see an educated black man portrayed in a film made in 1945. Not to mention the telegram lady. Peter Godfrey’s influence?

LikeLike