Gold (1934), directed by Karl Hartl. Movie night on Blu-ray on Monday, January 2.

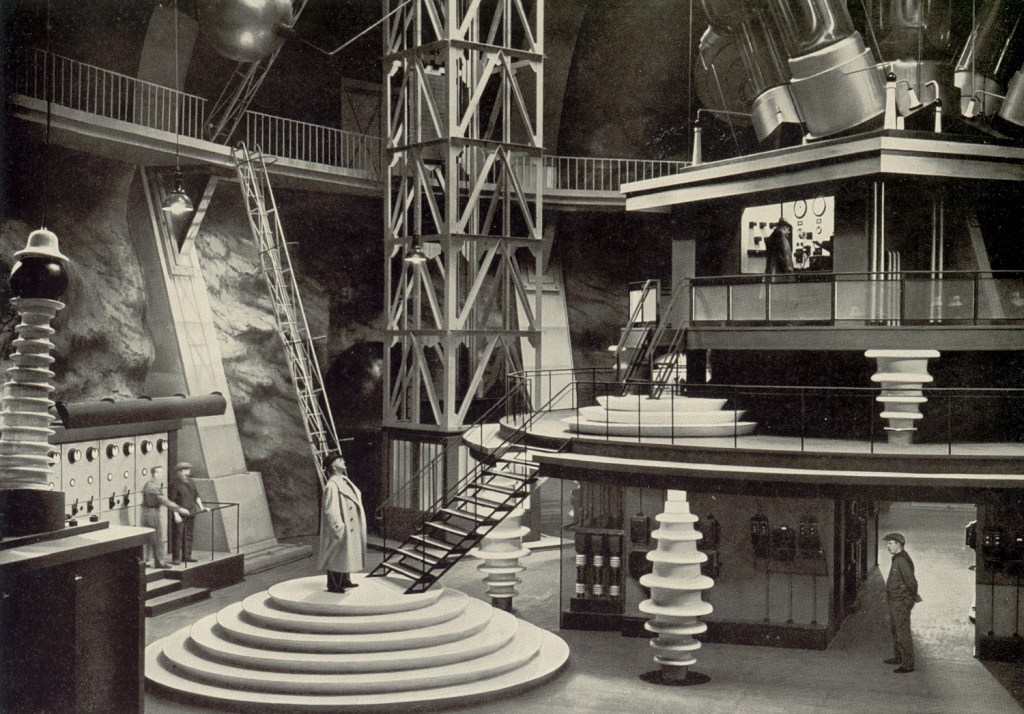

This bizarre, Nazi-era science fiction film is about a man who invents a machine that can turn lead into gold, whose partner (the actual brains behind the machine) is murdered by a wealthy Scot. That Scot kidnaps our hero (Hans Albers, whose popularity was such that the Nazis allowed him to continue working despite his Jewish wife) and then the hero plots to destroy the machine.

This was a fun, exciting, and bizarre movie, whose massive sets look, at the very least, inspired by Metropolis and maybe even were the reused sets from that famous silent film. Brigitte Helm, the robot in Metropolis, even has a large role here. There’s a lot of stuff about gold and its effect on the economy, which I’m sure was Nazi propaganda somehow (though aimed at the Scots?) and yet, according to most sources I’ve found, Albers wouldn’t work on a picture that pushed the National Socialists’ agenda.

After watching Colonel Blimp recently, I am struck by how winning wars changes opinions. I mean, the British have done a swell job of committing unbelievable atrocities and then getting away with presenting themselves as heroes–I mean, not just Colonel Blimp, but Zulu and The Man Who Would Be King are all movies in service to cheering on England’s bloody crimes in Africa and Afghanistan. And here, with Gold and other movies (most now available on DVD from Kino), we see movie, and other films, made by people caught in Germany who are understandably poisoned by their making art in such a climate. Fascinating.