The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, Criterion Channel at home on Xmas Eve.

Honestly, I love it when a movie moves me terribly and confuses me proper. When it comes to The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, perhaps it’s best to consider these two very different critics:

In the film, Blimp is honorable, kindly, decent, but helplessly old-fashioned. In truth, he probably believed in capital punishment, keeping the wogs in their place, flogging homosexuals, and a little charity for the poor. –David Thomson, Have You Seen…? A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films

This is a film about loss and longing, about creating the impossible and then setting it beyond your grasp. This is a film about home and the meaning of home, the meaning of self. This is a film which lies in the most human ways but tells remarkable, human truths… [it] is more poignant and savagely forgiving, more melancholy, troubling and revealing, than almost any other cinematic work I have encountered. –A. L. Kennedy, BFI Film Classics: The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

That first quote is from a cranky old white man whose opinions I admire but sometimes recoil from; the second is a white female novelist who considers herself a pacifist and, in life, would loathe Blimps (by her own admission).

God, I love that conflict, that slippery way one’s feelings, beliefs and opinions can’t quite reconcile with a story. See, I love The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. I think it was Barry Kryshka at the Trylon who also loves it and considers it a holiday film, and screened it years ago at the Trylon where it played to almost no one around the holidays. From then I was hooked, even as I was utterly baffled. Though it doesn’t take place during the holidays, or even in the winter, I like watching it in December. I’ve seen it a few times, never quite settling on any one feeling about it.

First, let me explain the name Colonel Blimp: no one in the film is named Colonel Blimp, it comes from a famous English comic strip that poked fun at fat old military men, Tories and beefeaters all. This strip coined the term “Colonel Blimp” for any old Englishman shouting about the good old days. The main character of the movie, who is a Colonel Blimp type, is one Clive Candy, and he is, as Thomson notes, repellent if he was truly real, despite being a kind man much of the time. However, we will never see this kindness challenged by any people with more, er, liberal modern attitudes, even those that existed at the time, never see his attitudes challenged by someone who disagrees deeply. Surely, Clive Candy is a man who would’ve hated Gandhi, to name but one.

Clive Candy is charming and heartfelt and loving, but even in the film he does a lot of stuff that’s just absolutely hideous–there are a pair of little montages that show the stuffed heads of animals he’s slaughtered appearing on Candy’s wall over the years, including a poor elephant and bunch of other unfortunates from Africa, India, all of the Queen’s holdings. This is supposed to be funny, or charming, all the slaughter of these animals.

On the surface, the story, which is a rambling tale told over many, many years (it’s almost three hours long) is really how Good Old Englishness should stand up to the horrors and unfairness of modern warfare, and that sort of fairness is reflected in the Jolly Old English way of life, which is warm, and loving, and kind. This point is challenged at the start by a young soldier who points out that the Nazis don’t play fair, so why should we? We being the English. I agree that fair play and being upstanding are good. And the film celebrates good citizens and what it means to have a rich life.

But the film is also more about death and friendship and the ravages of time on a human body and soul. Both Kennedy and Thomson note that there’s a powerful, so very powerful sense of deep, deep friendship in this film, of love for country that seems healthy and is based on fairness and kindness, and in this fantasy one desperately wishes the world were like this, everywhere. The film is melancholy, and it is one of the few films I’ve ever seen that really captures what it is to live a life and then watch, in bafflement, as life moves on and you begin to realize that you won’t–move on, that is. You have to accept change, accept that youth will now rule the world, accept that everything solid and real in your life is soon to crumble into dust. And as you begin to realize this, the color of life becomes even more rich and luscious, and that finite sense of existence is what makes life so heartbreakingly beautifuyl. I love that about Colonel Blimp.

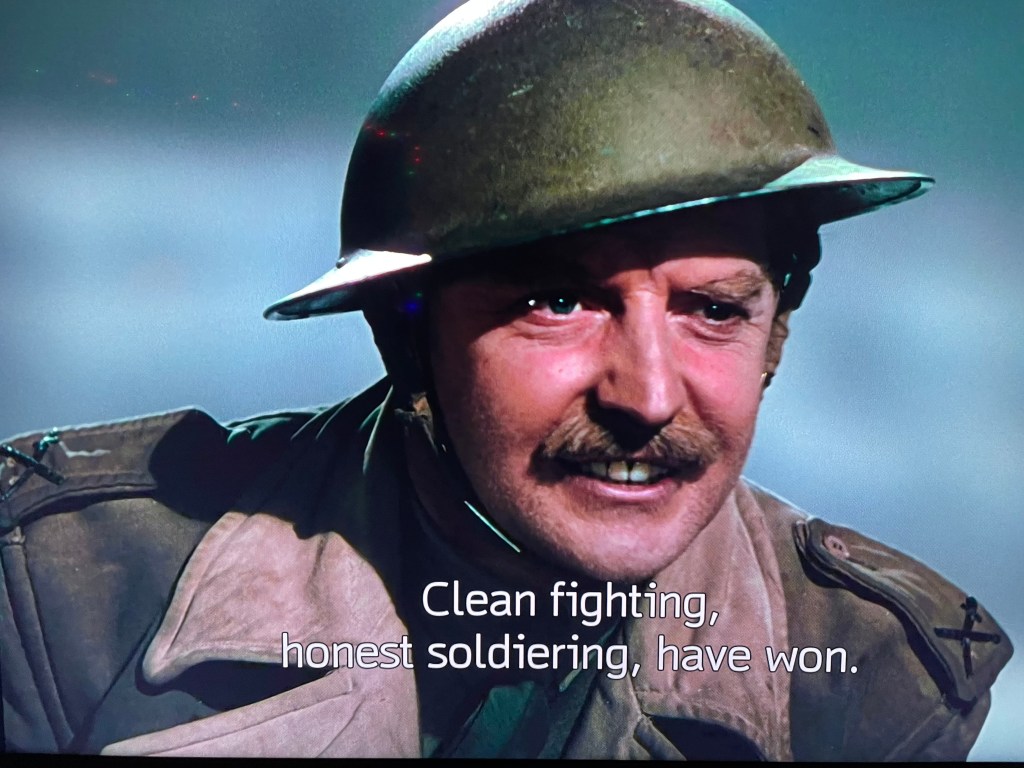

Still, some of it is a bit hard to take. Part of the plot concerns Clive Candy meeting a woman, whose spirit he will see in many other incarnations, and she is played by Deborah Kerr, three times. The first Deborah Kerr is Edith, who Clive meets and then introduces to a man who will become his best pal, Theo (Anton Walbrook), whom she marries; then another Deborah Kerr, Barbara, will marry Clive during the first World War; when both those ladies die, then a young woman during WWII, Johnny, will be on hand to drive Clive and Theo around, because they’re old men. Clive met that first Deborah Kerr when she writes a letter to him, calling him to Berlin. She wants a hero like Clive (he won the Victoria Cross) to come to Berlin to to tell off the Germans who claim that the British are killing women and children in the Boer War. Defying his superiors, who tell him to leave this to the government PR men, Clive heads to Berlin to set these bastards straight. After all, the Germans will go on to become atrocious warriors later, right? And later, in WWI, when the Allies finally defeat the Germans, Clive grits his teeth in joy that “right” has won over “barbarism”, that the first big one was won by the Allies being upstanding soldiers and the Germans and their clans being vicious beasts. Jesus Fucking Christ. The British atrocities in the Boer War were well known even then (they were literally doing exactly what they claim they’re not doing in the movie), and the same goes for World War I, in which no one was spared being utterly barbaric and vile.

And yet… the Archers (that’s Powell and Pressburger) made their films so gorgeous and full of life and love, brimming over with human feeling and using those deep colors and wonderful performers to express these emotions, so the movie definitely appears to be a triumphant celebration of what it is to be human. Kennedy points out that Pressburger was a Jew who escaped the Nazis and had significant loved ones perish under their hand, and he must’ve thought the British were just the epitome of kind souls. So it’s understandable. And the movie is good, so damn good.

But, I will tell you, I have also seen German movies, like Great Freedom No. 7, that celebrates life like the Archers. That movie was made in 1944. As in, under Nazi rule. It stars a man who remained in Germany while his Jewish wife hid in England, and had many elements that directly knocked the powers that be. It also has a brief moment with a pair of Black sailors (which is more than I can say for many Allied films, including Blimp and probably ever Archer film). So there you go.

My only point is: watch the movie. It’s gorgeous and lovely and compelling and leaves my heart aching. And if you hate it, for all the reasons mentioned (or others), I don’t blame you one bit.